Pray for South Sudan, Pray for Africa!

Top officials overseeing South Sudan’s military courts have resigned, saying high-level interference made it impossible to discipline soldiers accused of rape and murder amid the nation’s civil war.

The resignations of Brigadier General Henry Oyay Nyago and Colonel Khalid Ono Loki, according to a letter seen by various media networks, follow the resignations of a general and the minister of labour earlier this week.

Oil-rich South Sudan has been mired in civil war since 2013 when President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, fired his vice president Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer. Since then, fighting has increasingly fractured the world’s youngest country along ethnic lines, leading the UN to warn that the violence was setting the stage for genocide.

Nyago, advocate general and director of military justice, became the latest military official to pen a damning resignation letter accusing the President’s government of atrocities in the civil war. In another letter released on Saturday, Loki, the head of South Sudan’s military court, accused the army chief of extra-judicial arrests of citizens based on their ethnicity. Loki also accused Army Chief Awan of dismissing rulings against members of his own tribe accused of murder, rape and theft.

Both Nyago and Loki said soldiers were committing crimes without fear of punishment, particularly officers who were Dinka, the same tribe as the president and chief of army staff. The government has previously said soldiers who commit abuses are prosecuted. Officials have not provided any figures or details on such cases.

“Rape cases committed and being committed by your army and organised forces have become a daily game … you have recruited children compulsorily and ordered killing of war prisoners,” Nyago’s letter added.

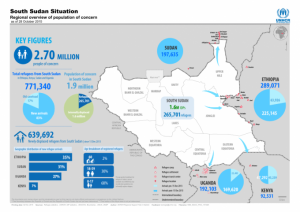

The conflict has forced more than three million of the nation’s 11 million citizens to leave their homes, creating pockets of severe malnutrition. There are 15,000 UN peacekeepers in South Sudan, but they have been criticised for not intervening when human rights abuses are being committed.

The Republic of South Sudan became the world’s newest nation and Africa’s 55th country on July 9, 2011, following a ‘peaceful’ secession from the Sudan through a referendum in January 2011. As a new nation, South Sudan has the dual challenge of dealing with the legacy of more than 50 years of conflict and continued instability, along with huge development needs.

At least 1.5 million people are thought to have lost their lives and more than four million were displaced in the ensuing 22 years of guerrilla warfare. Large numbers of South Sudanese fled the fighting, either to the north or to neighbouring countries, where many remain.

Independence did not bring conflict in South Sudan to an end. The 2013-2015 civil war displaced 2.2 million people and threatened the success of one of the world’s newest countries. Made up of the 10 southern-most states of Sudan, South Sudan is one of the most diverse countries in Africa. It is home to over 60 different major ethnic groups, and the majority of its people follow traditional religions.

Salva Kiir Mayardit became president of South Sudan – then still part of Sudan – and head of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in 2005, succeeding long-time rebel leader John Garang, who died in a helicopter crash. Mr Kiir was re-elected as president in multiparty polls in the south in April 2010. In July 2011, when South Sudan became independent, he became president of the new state.

Just two years later, however, the country was engulfed by civil war when Mr Kiir sacked his entire cabinet and accused Vice-President Riek Machar of instigating a failed coup.

The renewed conflict, in South Sudan is undermining development gains achieved since independence and worsened the humanitarian situation. Without conflict resolution and a framework for peace and security, the country’s longer-term development and prosperity are threatened.

Since the conflict began, almost 1 in 3 people in South Sudan have been displaced. Some 3.6 million citizens have been forced to flee their homes: more than 1.5 million people have escaped to neighboring countries in search of safety including Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda; resulting in Africa’s largest refugee crisis and more than 2.1 million are trapped inside the warring nation. South Sudan is now the third–most fled country in the world, behind Syria and Afghanistan.

Alongside the oil issue, several border disputes with Sudan continue to strain ties. The main row is over border region of Abyei, where a referendum for the residents to decide whether to join south or north has been delayed over voter eligibility. Inside South Sudan, a cattle-raiding feud between rival ethnic groups in Jonglei state has left hundreds of people dead and some 100,000 displaced since independence.

Since independence, relations with Sudan have been changing. Sudan‘s President Omar al-Bashir first announced, in January 2011, that dual citizenship in the North and the South would be allowed, but upon the independence of South Sudan he retracted the offer. He has also suggested an EU-style confederation. Essam Sharaf, Prime Minister of Egypt after the 2011 Egyptian revolution, made his first foreign visit to Khartoum and Juba in the lead-up to South Sudan‘s secession

South Sudan is a member state of the United Nations, the African Union, and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa. South Sudan plans to join the Commonwealth of Nations, the East African Community, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank.

The country is very young with two-thirds of the population under the age of 30. The 2009 national Baseline Household Survey also reveals that the country faces several human development challenges. Only 27% of the population aged 15 years and above is literate, with significant gender disparities: the literacy rate for males is 40% compared to 16% for females.

The infant mortality rate is 105 (per 1,000 live births), maternal mortality rate is 2,054 (per 100,000 live births), and only 17% of children are fully immunized. 55% of the population has access to improved sources of drinking water. Around 38% of the population has to walk for more than 30 minutes one way to collect drinking water, and some 80% of South Sudanese do not have access to any toilet facility

The U.N. appealed for $1.6 billion to assist 4.6 million people in need in 2015, but the effort was only 62 percent funded. Only 88 percent of the $1.29 billion requested for 2016 has been funded.

Many humanitarian organizations, including Mercy Corps, are partnering with the U.N., using both private contributions and funding from the international community, to address the urgent needs of innocent people in South Sudan.

“I worry about my children. I don’t know when this war will stop,” says Mary. “There is no good news. There is only talk of fighting and attacks. The children have no food to eat. The children have no school to go to. Our children are becoming soldiers.”

Across the country, children can’t learn, people can’t work, farmers can’t plant — all they can do is hope to survive until there is an end to the vicious fighting.

In addition, the country has very little formal infrastructure — roads, buses, buildings — which makes it difficult to transport food and supplies. Many towns and villages become inaccessible during the annual rainy season due to closed airstrips, washed out roads or lack of roads altogether, sometimes limiting any delivery of humanitarian aid to the isolated areas that need it most.

TIMELINE

Some key dates in South Sudan’s history:

1956 – Sudan becomes independent but southern states are unhappy with their lack of autonomy. Tensions boil over into fighting that lasts until 1972, when the south is promised a degree of self-government.

1983 – Fighting starts again after the Sudanese government cancels the autonomy arrangements.

2011 – South Sudan becomes an independent country, after over 20 years of guerrilla warfare, which claimed the lives of at least 1.5 million people and more than four million were displaced.

2012 – Disagreements with Sudan over the oil-rich region of Abyei erupt into fighting, known as the Heglig Crisis. A peace deal was reached in June 2012 that helped resume South Sudan’s oil exports and created a 10km demilitarized zone along the border.

2013 – Civil war breaks out after the president, Salva Kiir Mayardiit, sacks the cabinet and accuses Vice-President Riek Machar of planning a failed coup. Over 2.2 million people are displaced by the fighting and severe famine puts the lives of thousands at risk.

2015 – Warring sides sign a peace deal to end the civil war, but the conflict continues.