One Country One Peace ?

Half a century on from the 30 May declaration of independence from Nigeria, calls for secession are growing again.

The early years of independence, gained in 1960, were hugely tumultuous for Nigeria. The new country contained within it a vast diversity of peoples, and tensions arose along regional, ethnic and religious lines.

Tussles over power escalated in January 1966 when a coup d’état led to the murder of several northern political leaders, including the Prime Minister and the Premier of the northern region. A few months later in July, northern army units orchestrated a counter-coup which led to the death of the military head-of-state General Aguiyi Ironsi.

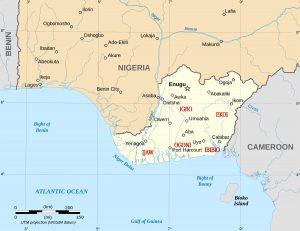

Distrust and animosity between different groups around the country intensified. In September 1966, over 30,000 Igbos – who originate from the south-east of Nigeria – were killed in the north. Retaliatory attacks in the south led to the deaths of many northerners.

“There was sadness in the heart of every single Igbo family,” says Ejiofor. “Nobody in eastern Nigeria had not lost somebody.”

As protests led to further bloodshed and inter-communal violence escalated, dialogue was called. Hosted by Ghana, Nigeria’s regional leaders and delegates from the federal government met in January 1967. In the meeting, easterners called for greater control over their own resources – which includes vast oil reserves – and the so-called Aburi Accord was struck.

In the following months, however, the agreement broke down.

“Confederation was the last hope of the Igbo man,” says Ejiofor. “We already suffered a lot. There was no healing for the easterners.”

On 30 May 1967, the Eastern Region declared independence as the Republic of Biafra.

“When the declaration was made, we were all glorifying God. There was jubilation in the entire south-eastern region,” Ejiofor recalls.

“No one envisaged what followed.”

What followed was a brutal and devastating civil war as federal forces and Biafrans engaged in bloody battle. Ejiofor was appointed Aide-de-camp to the leader of the secessionist struggle, Odumegwu Ojukwu. He was only 21.

There were offensives and counter-offensives, but from 1968, the Nigerian government embarked on strategy to blockage the region. Medical and food supplies were cut off, leading to a humanitarian crisis. In the severe famine that ensued, some estimate that two to three million people starved to death – mainly women and children.

“When I close my eyes, I hear the voices of dead children and their bones, and the sadness of the faces of refugee mothers,” says Ejiofor.

In January 1970, the embattled Biafrans surrendered and renounced the call for secession.

In the three decades following the end of the conflict, the demands for independence went silent. But the grievances of the region did not go away. There has never been justice for the millions who died in the war and famine, an atrocity that many see as genocide. And many easterners have continued to argue that the region is marginalised in the federal allocation of resources and appointment of national leaders.

According Victor Ukaogu, professor of history at the University of Nigeria, the problems that led to the war were never resolved.

“This is the only country that has had a civil war and not a lesson was learnt from that war,” he says. “If you study thoroughly the history of the civil war, some people may actually go to [the International Court of Justice in] The Hague to face trial for war crimes. Definite genocide took place.”

In 1999, a few months after Nigeria’s return to multi-party democracy, a new group emerged reviving calls for Biafran independence. It was named the Movement for the Actualisation of Independent State of Biafra (MASSOB) and was established by Ralph Uwazuruike, an India-trained lawyer who sought the resurgence of Biafra non-violently.

The group introduced a Biafra currency and passport. Activists also ended up clashing with government forces on a few occasions, leading to the deaths of some members. In 2005, the government arrested Uwazuruike on treason charges, but released him in 2007.

Renewed calls

In 2014, another secessionist group, known as the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), took up the struggle. Founded by Nnamdi Kanu in the UK, it also adopted a stance of non-violence and has acquired significant support among many people in south-east and south-south states.

IPOB has been able to spread its message in large part thanks to Radio Biafra, which was established by Kanu in 2009 and broadcasts to Nigeria from London. The station can be streamed live from many countries. Across the south east of Nigeria, farmers, traders, drivers, teachers and students gather to listen to and discuss its shows.

This has helped drive the issue of independence back up the agenda, especially among younger people.

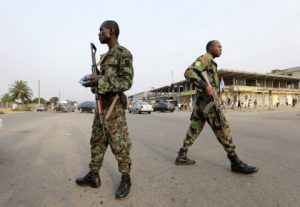

IPOB has also organised large demonstrations, some of which have been confronted by police. At last year’s 30 May celebrations marking the anniversary of the independence declaration, over 60 members of the group were killed according to Amnesty International. The body says that between August 2015 and August 2016, “security forces have killed at least 150 members and supporters of the pro-Biafra organization IPOB and injured hundreds during non-violent meetings”.

In October 2015, Kanu was arrested on charges of treason after flying to Lagos. Human rights groups and politicians called for his release, but he was held without bail despite multiple court judgements granting him bail. It was only in April 2017 that Kalu regained his freedom.

As the 50th anniversary of the declaration of Biafran independence approaches on the 30 May, some see echoes of the dynamics half a century ago. Many observers, such as public policy expert Aye Dee, criticise the government’s strategy of clamping down on pro-Biafra protests and imprisoning Kanu rather than addressing their complaints.

Retired headmaster Paul Ukachukwu , who lived through the civil war, suggests that the government is failing to listen. “An Igbo man has no place in Nigeria since the northerners having tasted power are not willing to permit any other region to have equitable political power,” he says. “No one would ask for another nation once they begin to experience fairness.”