More Black on Black Crime! What are your thoughts?

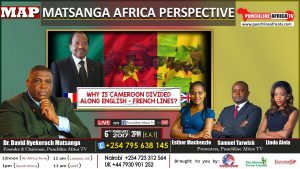

In Cameroon, a fight over colonial languages is dividing the country. English-speaking regions of Cameroon, once divided between France and Britain, have been protesting for months against the dominance of the French language—the official language in four-fifths of the central African country.

A single student out of 4,000 showed up on the first day of the new term at one high school in Bamenda, the English-speaking city at the heart of a deadly conflict in Cameroon over language in this bilingual West African country.

Teachers have joined a strike led by lawyers resentful over the official use of French in the English-speaking part of the country. Recent protests have called for “ghost town” strikes in major cities. The government shut down the internet in the English-speaking region, digital advocacy group Access Now has said.

Tensions are so high that 10 people were killed in demonstrations over language discrimination in Bamenda in December, according to a coalition of human rights groups based in the city. The government sent in 5,000 troops to stabilize the city.

Clashes during mass protests in November and December left several dead, more than 100 missing, and an undisclosed number of protesters imprisoned. Anglophones account for about 20% of Cameroon’s 23 million people and according to the Cameroonian constitution, both English and French are official languages with “the same status.” “The State shall guarantee the promotion of bilingualism throughout the country,” the constitution, adopted in 1972, says.

Two officials with the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium have been charged with terrorism and rebellion against the state for their role in the recent protests and face the death penalty if convicted. The government has banned the consortium’s activities. Another activist, Bibixy Mancho, faces the same charges.

The protests began late last year when lawyers asked that French-speaking judges be transferred out of English-speaking regions, saying justice cannot be rendered when the judge, the lawyer and the suspect cannot communicate. When the lawyer’s requests were not granted, they went to the streets and refused to defend clients in court.

In 1961, a vote was held in what are today’s northwest and southwest English speaking regions of Cameroon. The referendum was over whether to join Nigeria, which had already obtained independence from Britain, or the Republic of Cameroon, which had obtained independence from France. Voters elected to become part of French speaking Cameroon, and the country practiced a federal system of government. English and French became the official languages of Cameroon.

Ebune Charles, historian at the University of Yaounde, says since 1972, when a new constitution was adopted replacing a federal state with a unitary state, French speaking Cameroonians have failed to respect the linguistic and cultural nature of the minority English speaking Cameroonians.

“We were supposed to have predominantly English speaking administrators in the predominantly English speaking regions of the northwest and the southwest, and that is not the case,” Ebune said. “We were expecting official documents signed in both languages; that is not the case. Presidential decrees come only in one language. If you look at the level of the military, that is where it is so scandalous. It is just in one language but we are in a bilingual country.”

Charles also pointed out that the country’s currency is printed only in French, notice boards even in the English speaking regions are mostly in French, and more than 70 percent of radio and TV programs in the state media are in French.

The ongoing protests started when lawyers in the English speaking regions asked for French speaking judges who are not of the common law system to be transferred out of courts in those regions. They declared that justice can’t be rendered when the judge, the advocate and the suspect can’t communicate.