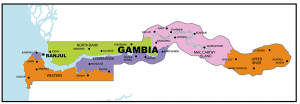

Gambia Gettin to the Money Real Quick!

Yesterday, UK foreign minister Boris Johnson visited The Gambia, marking another example of the country’s improved relationships with international partners under the new administration of President Adama Barrow.

Johnson’s visit follows that of EU commissioner Neven Mimica last week, who announced a €225 million ($237 million) aid package for the West African country with a population of just 2 million.

High-profile visits like these signal that democratic transitions in West Africa are rewarded quickly and generously. And after years of external isolation and internal mismanagement, The Gambia requires strong partnerships to find its footing as West Africa’s newest democracy.

Nonetheless, discourses and motives of renewed partnerships should be subject to scrutiny by The Gambia‘s new leadership. For the good of the country, it is imperative that equality and respect are at the heart of these aid deals and cooperation agreements.

For example, in 2016, The Gambia received €14.9 million ($15.7 million) from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, a resource set up to curb “ongoing unprecedented levels of irregular migration” into Europe. Of this package, €11 million ($11.6 million) went to a youth employment project and €3.9 million ($4.1 million) towards the “return and reintegration” of Gambian migrants to the EU.

Funding from the Emergency Trust Fund primarily intends to halt the influx of Gambians crossing into Europe, and such a partnership is potentially marred by an exclusionary undertone – namely that Gambian migrants are undesirable within Europe’s borders and that pumping money to keep them at home is the solution.

Though Gambia’s new EU aid package will not necessarily be drawn from the same migration trust fund, similar ideological underpinnings could exist in future projects and should be scrutinised by Gambian counterparts.

Who holds the Power?

In terms of the UK, Johnson’s pronouncement of re-entry into the Commonwealth of Nations is well received by the local population, many of whom still mourn the country’s exit in 2013. “Without the Commonwealth, who else do we have?” asked an administrator at a British school in Fajara.

This optimism is understandable. Unlike aid packages, Commonwealth membership creates opportunities for Gambians to live, work and study in the UK and enhances the rights of Gambians abroad. For instance, Commonwealth citizens residing in the UK can vote, while Chevening Scholarships, among other funding sources, will once again enable bright young Gambians to study in world-class universities.

During his visit, Johnson also confirmed that the UK Department for International Development (DFID) funds, whose bilateral aid programme has been halted since 2011, would soon restart. He suggested that education would be key point of focus.

However, echoing the EU Trust Fund‘s mandate, Johnson also underscored the importance of security for UK-Gambia relations, noting that “tackling the migration crisis is absolutely vital for Europe as well as for Africa”.

While Johnson’s press conference had a light-hearted tone, at one point referring to the former president as a “Jammeh Dodger”, the underlying messages regarding security and migration should be taken seriously.

A broad swath of the Gambian population embraces Commonwealth membership and foreign partnerships as a symbolic undoing of damage accrued during Yahya Jammeh‘s rule. However, taking a careful and critical stance on membership in what Jammeh once called a “neo-colonial” institution may not be entirely misguided.

Such partnerships are almost always accompanied by politics, pressures and strings attached. And in a very small and very poor country like The Gambia, power imbalances have the potential to become magnified. As such, the new government must ensure that the nation’s trajectory follows its own vision and objectives, and not those of international donors.

As a new democracy, such independence is even more important in establishing a homegrown national agenda. Furthermore, it will ensure candidates of the new ruling coalition remain legitimate and avoid accusations of serving as a puppet of international interests. In Côte d’Ivoire, President Alassane Ouattara still grapples with accusations of illegitimacy due to his relationship with France before and after the 2010 elections and his continuation of neoliberal policies that benefit the country’s former colonial power.

Aid and development work can improve the lives of people in The Gambia. The danger, however, is in viewing this cash influx as a magic bullet. The reality is that The Gambia has its work set out and it will take years to rebuild and create new institutions and capacities. No amount of money or memberships in international organisations will accomplish this.

Johnson’s visit to The Gambia marks the end of a long period of economic stagnation and seclusion and the beginning of what locals are calling “The New Gambia“. As these streams of money flow in, international partners should carefully consider the underlying aims of their agendas and avenues of their enactment.

But more importantly, the Gambian government and local organisations that receive international aid must remain strong and predefine where, how and to what ends they require support for the country’s own vision and agenda. Source – Dr Marika Tsolakis is a Postdoctoral Fellow at UCL Institute of Education and SOAS, funded through the ESRC Global Challenges Research Fund. Her research focuses on youth, non-formal learning and political discussion in West Africa. She is currently based in Fajara, The Gambia.